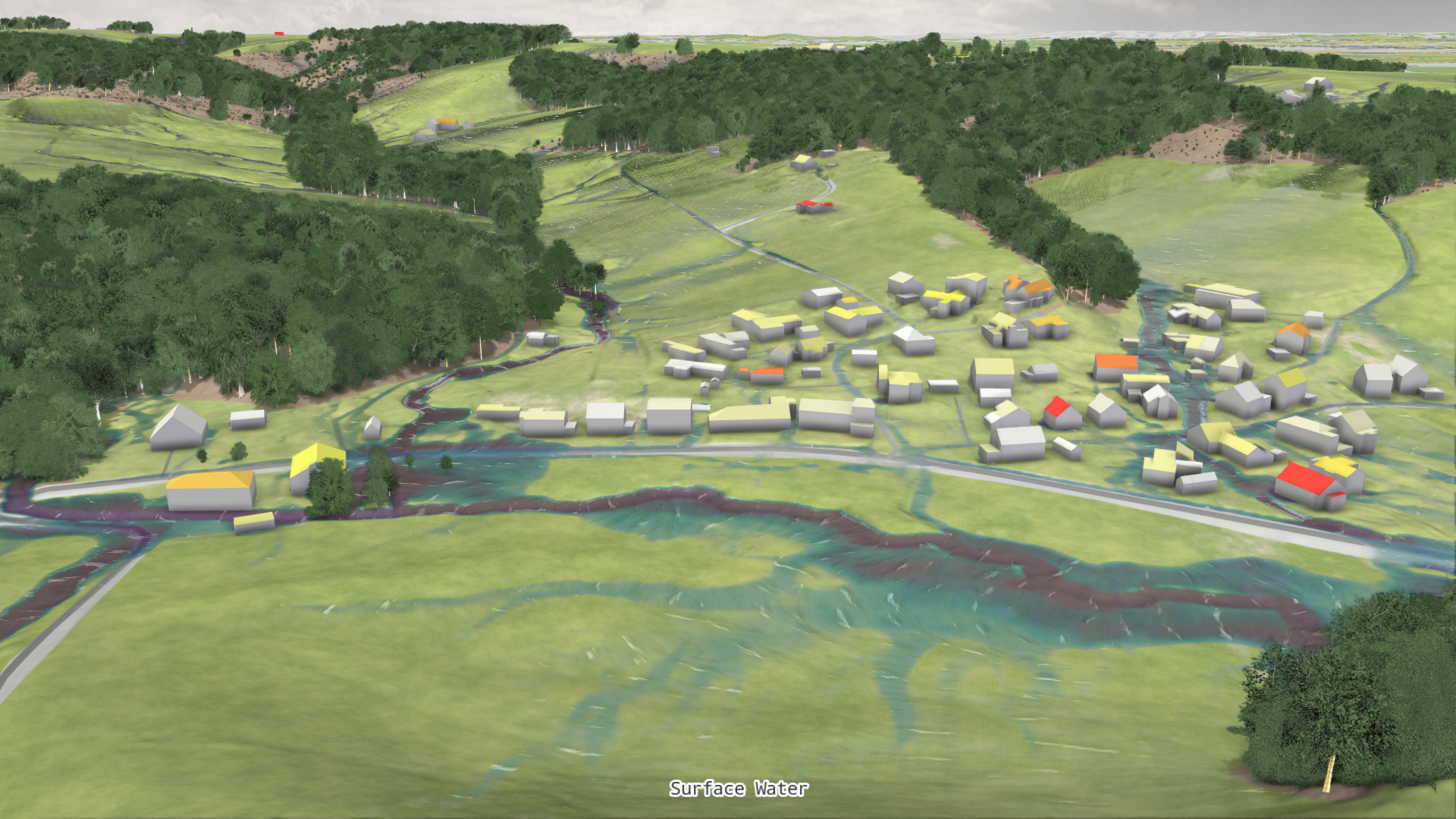

2D Hydrodynamic Surface Model

The surface water simulation in scenarify uses a state-of-the-art solver for the two-dimensional (2D) shallow water equations. The equations are discretized using an explicit finite volume method on a structured uniform Simulation Domain. The temporal discretization is given by the maximum simulation time step computed from the CFL condition. Spatially distributed friction is calculated with the Gauckler-Manning-Strickler formula by setting the roughness parameters according to land use, see the page on Roughness. The surface water simulation has been extensively validated through analytical solutions, laboratory experiments, and historical events.

The Shallow Water Equations

The full time-dependent Shallow Water Equations (SWE) describe the surface flow and are written in vector form as:

where \( \mathbf{U} = [h, hu, hv]^T \) is the vector of conserved variables. Here, \( h \) is the water height, \( hu \) is the discharge along the \( x \)-axis, and \( hv \) is the discharge along the \( y \)-axis. The flux functions \( \mathbf{F} \) and \( \mathbf{G} \) are:

The bed slope term \( \mathbf{S}_b \) models fluid acceleration due to gravitational forces while the friction term \( \mathbf{S}_f \) models bed friction:

Here, \( u \) and \( v \) are the average flow velocities in \( x \) and \( y \) directions, \( g \) is the gravitational constant, \( b \) is the bed level, and \( n \) is the Manning friction coefficient.

To integrate the interception and infiltration processes of the runoff model and the sewer model with the surface flow, coupling terms \( \mathbf{S}_r \) and \( \mathbf{S}_s \) are added on the right-hand side of the SWE. The sewer coupling term \( \mathbf{S}_s \) accounts for the specific sewer exchange discharge \( q_e \) (m/s). The source terms \( \mathbf{S}_r \) and \( \mathbf{S}_s \) are given by:

The runoff rate \( r_e \) (m/s) is the difference between the effective precipitation rate and the effective infiltration rate.

Accuracy and Numerical Schemes

The spatial discretization of the SWEs uses the Finite Volume Method (FVM) on a uniform Cartesian grid. The conserved variables \( \mathbf{U} \) are discretized as cell averages, leading to a system of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) for the cell averages \( \mathbf{U}_{j,k}(t) \).

For overland flow simulation, either a first-order accurate or a second-order accurate scheme can be employed. The first-order CN scheme preserves lake-at-rest steady states and handles flow states across bed discontinuities better than the original hydrostatic reconstruction scheme. The second-order BH scheme achieves second-order accuracy in space through a minmod limiter set to 1 for robust and fast simulations.

The surface flow is discretized in time by the explicit Euler method for the first-order CN scheme with a CFL constant of 0.5, ensuring numerical stability and non-negativity of water depths. The second-order BH scheme is integrated in time with Heun's method and a CFL constant of 0.25. The CFL condition restricts the time step \( \Delta t \):

where \( \sigma \) is the maximum numerical speed and \( \Delta x \) is the uniform grid resolution. Both the first-order scheme and the second-order scheme conserve mass and preserve lake-at-rest steady states.

The friction source term \( \mathbf{S}_f \) is evaluated semi-implicitly by splitting it into a coefficient-wise product of an implicitly evaluated state and an explicitly evaluated friction term, see Buttinger et al. (2019).

Hint: Based on the findings of Horváth et al. (2020), we recommend using Interactive Accuracy (the first-order scheme) for heavy rainfall simulations and planning, and High Accuracy (the second-order scheme) for creating hazard maps of river floods. You can switch between Interactive Accuracy and High Accuracy in the Surface: Simulation Model category of the Simulation Settings Panel. For more details, check out the task-based workflow Choosing the Right Accuracy for Your Task.

Boundary Conditions

We remark that the following boundary conditions (BCs) take into account the regime of the flow, e.g., if the state at the boundary is subcritical or supercritical. In other words, we set boundary values only on the characteristics that are entering the computational domain. The following boundary conditions are also described in Horváth et al. (2020).

Free Outflows

At the boundary of the computational domain, where the simulation requires artificial truncation of water flow, free outflow boundary conditions (BCs) are applied. These BCs are employed when no specific data is available at the outflow boundaries, and continuity-based extensions are utilized. The free outflow BCs are akin to zero-order absorbing BCs, as described by Ehrhardt (2010). In this context, the incoming characteristic of the flow is set to zero to simulate the absence of data beyond the computational domain. Additionaly, free outflows do not allow any inflow, so water does never flow into the domain at a free outflow boundary.

Walls

In urban regions, buildings and other impermable structures can completely block water flow. In such cases, wall BCs are used to define these fluid–solid interfaces between valid and wall cells. For walls, the key concept is to establish a boundary flux \( F(U_I) \) where the interface state \( U_I \) satisfies specific BCs based on numerical and physical principles. At a wall boundary, there is no flow across the interface, so the normal velocity vanishes, resulting in: \( hu_I = 0 \). Similarly, a boundary condition is determined for a prescribed water depth \( h_I \) at each interface, given by \( h_I = w_g - B_I \). In our simulations, we adopt the approach of Ghidaglia and Pascal (2005) to compute these boundary conditions for specified water heights and walls.

Inflows and Outflows

Inflow and outflow boundary conditions (BCs) are crucial in simulating river floods. Real-world hydrograph data typically include time series of water levels and discharge values. These data are prescribed as upstream and downstream BCs at inflow and outflow locations. Hydrograph data are often obtained from gauging stations and provided as scalar values: total discharge \( Q_g \) and water level \( w_g \).

For water-level data, each cell receives the same prescribed level. For discharge data, values are distributed along the rasterized hydrograph interfaces assuming a constant velocity vector normal to the cross-section. At each hydrograph interface \( I \), a discharge \( q_I = Q_g \cdot p_I \) is prescribed, where \( p_I \) represents the proportional share of this interface relative to \( Q_g \). This proportion \( p_I \) depends on the cross-sectional area \( A_I \) of the flow at interface \( I \), relative to the overall cross-sectional area \( A \). The value of \( p_I \) is updated at every time step based on the current water level.

To ensure mass influx equals the prescribed discharge, the inflow boundary flux must satisfy: \( F^h_I = q_I \) (x-dimension) and \( G^h_I = q_I \) (y-dimension). This boundary flux is determined from the solution of a linearized Riemann problem with prescribed interface discharges \( (hu)_I = q_I \). For the y-dimension, it involves a continuous extension of the y-discharge. For details, see Pankratz et al. (2007).

GPU Implementation of the Surface Water Model

The spatial discretization of surface flow with the Finite Volume Method (FVM) allows for straightforward parallelization on structured grids. The GPU implementation uses the CUDA platform of NVIDIA. In CUDA, parallel tasks are organized into thread blocks, each associated with one cell. A block size of 16 by 16 cells ensures high GPU utilization. The GPU implementation handles data dependencies with on-chip memory for fast processing of the computational stencil within the blocks. Both surface state and infiltration state are stored in single-precision floating-point variables to reduce memory burden and improve computational speed. For implementation details, the reader is referred to Horváth et al. (2016).

References

Buttinger-Kreuzhuber, A., Horváth, Z., Noelle S., Blöschl, G., and Waser, J. 2019. A fast second-order shallow water scheme on two-dimensional structured grids over abrupt topography. Advances in Water Resources 127: 89–108.

DOI: 10.1016/j.advwatres.2019.03.010

Ehrhardt, M. 2010. Absorbing boundary conditions for hyperbolic systems. Numer. Math. Theory Methods Appl. 3 (3): 295–337.

DOI: 10.4208/nmtma.2010.33.3.

Ghidaglia, J.-M., and F. Pascal. 2005. The normal flux method at the boundary for multidimensional finite volume approximations in CFD. Eur. J. Mech. B. Fluids 24 (1): 1–17.

DOI: 10.1016/j.euromechflu.2004.05.003

Horváth, Z., Perdigão, R.A., Waser, J., Cornel, D., Konev, A., Blöschl, G. 2016. Kepler shuffle for real-world flood simulations on GPUs. Int. J. High Perform. Comput. Appl. 30 (4): 379–395.

DOI: 10.1177/1094342016630800

Horváth, Z., Buttinger-Kreuzhuber, A., Konev, A., Cornel, D., Komma, J., Blöschl, G., Noelle, S., Waser, J. 2020. Comparison of fast shallow-water schemes on real-world floods. J. Hydraul. Eng. 146 (1): 05019005.

DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)HY.1943-7900.0001657

Pankratz, N., J. R. Natvig, B. Gjevik, and S. Noelle. 2007. High-order well-balanced finite-volume schemes for barotropic flows: Development and numerical comparisons. Ocean Modell. 18 (1): 53–79.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ocemod.2007.03.005